For the business of shipping on the Great Lakes, one thing that has changed very little is preparing a vessel for winter lay-up. From the early steamships of the 1800's, to the giant freighters of today, winterizing a large vessel is a big and very important job.

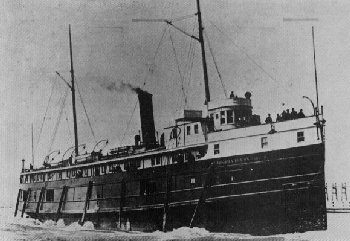

Taking good care of their fleet was very important to the Graham and Morton Transportation Company. This old and trusted steamship line had an excellent safety record spanning decades, going back to its beginning in the mid- 1800's. Most of the G&M steamers, though modern for their day, had been the slow and awkward side wheelers. Their newest vessel, the Chicora, was a sturdy propeller driven ship capable of speeds up to 16 knots.

The Chicora was launched on June 25, 1892 by the Detroit Drydock Company, and she was designed to be extra heavy duty with one thing in mind, 'extending the Lake Michigan shipping season into a year around business.' The Chicora was built with a heavy beam and strong framing timbers capable of pushing though Lake Michigan pack-ice without problems. Even so, shipping on the Great Lakes had proven to be a very risky business, especially in the winter months!

With a history that documents the loss of scores of ships, at the cost of hundreds of lives, and millions of dollars, insurance costs had become too high to run the Chicora during the winter as originally planned.

In 1894, after the vessel had been prepared for winter lay-up, and with only the winter watchman on duty, Milwaukee shippers asked that the Chicora be pressed into service once again. This request came to the G&M owners late in December. The shippers were looking to ship a cargo of bagged winter flour. The large shipment was to be loaded in Milwaukee, then freighted to the Benton Harbor dock.

To make the crossing more profitable, and to further justify taking the ship out of lay-up, regular freight customers as far away as Kalamazoo were informed of mid-winter voyage. Like a campfire story told again and again, the story of the Chicora's fateful voyage and her final cargo has been glamorized to a point, where I'm not sure the exact truth is known. In addition to the tons of bagged flour, some have claimed she carried everything from barrels Milwaukee whisky and beer, to even a shipment of $50,000.00 in gold coins. However, I must point out that the historians and the actual known records say, "not so."

After G&M workers removed the protective coverings from the pilot house windows and the huge fresh air intake-vent openings, other members of the crew readied her massive steam engine for the winter run. All of the hard work of her earlier winterizing had to be undone.

Steam pipes that had been

opened

and drained, now had to be closed and refilled. Her huge twin Scotch

boilers

which were also drained for winter, and her coal bunker, were refilled.

Fittings were cleaned of the heavy protective grease that was used for

storage, and all oil reservoirs refilled. Huge bearing caps for the

crankshaft

and propeller shafts were removed so the the giant bronze bearings

could

be flooded with fresh oil to avoid scoring at start up. All of this was

hard work for the engineer and his crew. Hard but important work that

had

to be done, and done right, to assure the safe operation of the engine.

Engine failure during a January trip could spell disaster!

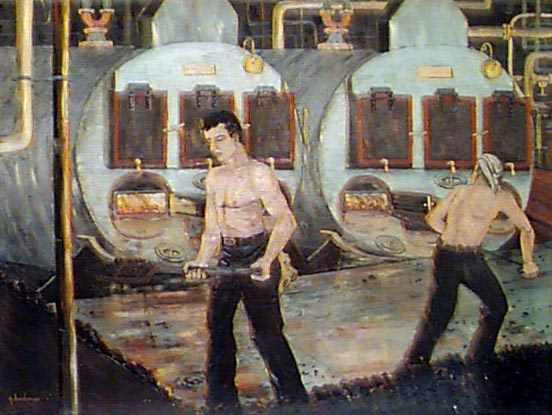

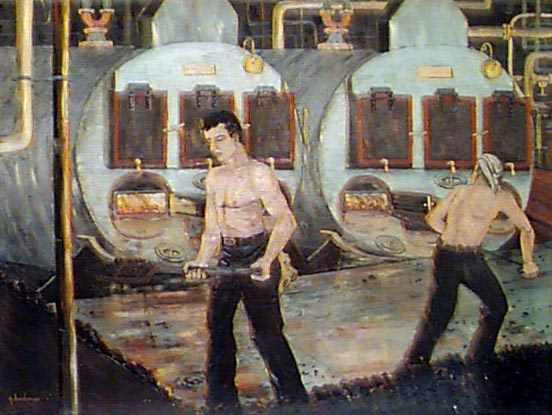

Firemen stoke the Chicora's Twin Scotch boilers with coal as she makes

way through Lake Michigan's pack ice.

Enough time had lapsed,

since what was believed to be her last trip until spring, that some of

the crew had

made long trips to their homes for the winter. Because of this, Captain

Edward Stines

found himself sort of crew members. In order to complete his crew list,

he signed-on his own 23 year old son Benjamin as second mate.

Just hours before she was

ready to leave, a freight train from Kalamazoo arrived with several

cases of patent bitters medicine from Kalamazoo's B. Desenburg

& Co. Wholesale Grocers , dry goods, newsprint rolls and other

Kalamazoo paper products, as well as 6 passengers for Milwaukee.

The Chicora left the

Michigan

dock for Milwaukee on January 19th and arrived without problems. After

the dock crews completed their unloading, their real work had just

started! Wagon load after wagon load of 100 pound cloth sacks filled

with winter four was unloaded from rail cars, rolled onto the Chicora,

where it was then stacked across the floor of the ships cargo area. The

bags were stacked 8 high, 20 deep and 20 across, --- back

breaking work! It was planned that after reaching Benton Harbor, the

cargo was to be shipped across Michigan by rail to mills in Kalamazoo,

Battle Creek and on to bakeries as far east as Detroit.

The ship's crew was anxious to complete the trip and return to the warmth of their homes. On January 21st, the day of her departure from Milwaukee, the day started out cold but otherwise pleasant--- but trouble was brewing! Even though the heavy cargo was nowhere near the Chicora's maximum capacity, the ship seemed to labor hard under her load and shudder as she departed the dock.

Back in Benton Harbor, John Graham, the ship's owner, had been watching the barometer and noticed that it was falling fast! Concerned for the ship and her crew, he wired the agent in Milwaukee with instructions to hold the ship at dock, but the telegraph messenger arrived ten minutes too late. He was in time to just catch a glimps the distant black cloud of coal smoke coming from the Chicora's stack on the horizon.

Only 2 hours into her return trip, she was pounded by ice and tossed with huge waves, the Chicora undoubtedly fought the storm for hours that afternoon and lost. The Chicora was never heard from again. She carried 23 crew members and one passenger to their deaths somewhere in Lake Michigan.

Captain Henry Stines, of the Goodrich Line steamer 'City of Ludington,' spent two days searching for his brother and nephew after the storm, but found no trace of the vessel or her crew. All that came ashore later that year were a few empty flour sacks printed with batch numbers and shipper information which clearly identified it as the Chicora's cargo, some bulwarks with the ship's name, as well as the ships mast, which washed ashore near Saugatuck Michigan.

I understand the mast was used in Douglas (some reports say Glen) as a flag pole. Today, I'm told the mast is on display at the Allegan County Museum.

Most ship wrecks come complete with some 'note-in-a-bottle' stories and the Chicora is no exception. The first bottle was discovered on April 14th and the note read, "All is lost, could see land if not snowed and blowed. Engine gave out, drifting to shore in ice. First Mate and Clerk are swept off. We have hard time of it. 10:15 o'clock.

One week later, a jar washed up in Glencoe, Illinois with a note, "Chicora engines broke. Drifted into trough of sea. We have lost all hope. She has gone to pieces. Good Bye. McClure, Engineer."

Divers from Holland Michigan thought they had found the Chicora in 2001 but it turned out to be different ship.... another of the 5000 wrecks in the Great Lakes.